Last year, I participated in a winter school offered by Greek Studies on Site called Athens through the Ages. A couple days ago, I read Sohrab’s Ahmari’s book The New Philistines (Provocations): How Identity Politics Disfigures the Arts and this book took me right back to juxtaposed experiences at the Byzantine Museum and the Kolonaki Gallery in Athens.

There were only four students in the winter school, plus the instructor. Toward the end of our ten days together, we visited the Byzantine Museum. One of the highlights of this experience happened when Georgia, Laura, and I were observing an icon of the Crucifixion. I recounted to them a story about a time I was visiting the Uffizi in Florence and decided to ask a young child who was looking up at a busy scene of the Nativity, “Where would you like to be in the scene?” The little girl pointed to a bird perched up high and said that she would like to be that bird so that she could have a good view. Georgia and Laura considered this a good exercise and asked me where I would like to be in the scene before us.

I pointed to Mary Magdalene who was right beneath Jesus’ feet, looking up imploringly and touching His feet lovingly. Georgia then asked Laura where she would be. Laura chose a woman in red, supporting Mary in her grief and catching her fall in a tender embrace. Then, at the next moment, Bruno entered the room in which we stood. We explained to him what we had been doing and then we asked him where he would be. He pointed to a man with a beard on the periphery and when we asked his reason he said, “Because he looks Jewish and I don’t really believe.” A few minutes later, from a different part of the museum, Ryan came in and, again, we explained our activity. However, this time I asked Ryan to guess the figures with which each of us had related. He guessed Mary Magdalene for me, Mary for Laura, and the man directly next to the one Bruno had chosen for Bruno.

As there are many figures in this icon, we were all amazed. It was a sign that we had gotten to know one another quite well during the intense days we had shared in Athens. We determined that there could be no better, sweeter note on which to end and so we left the museum together then.

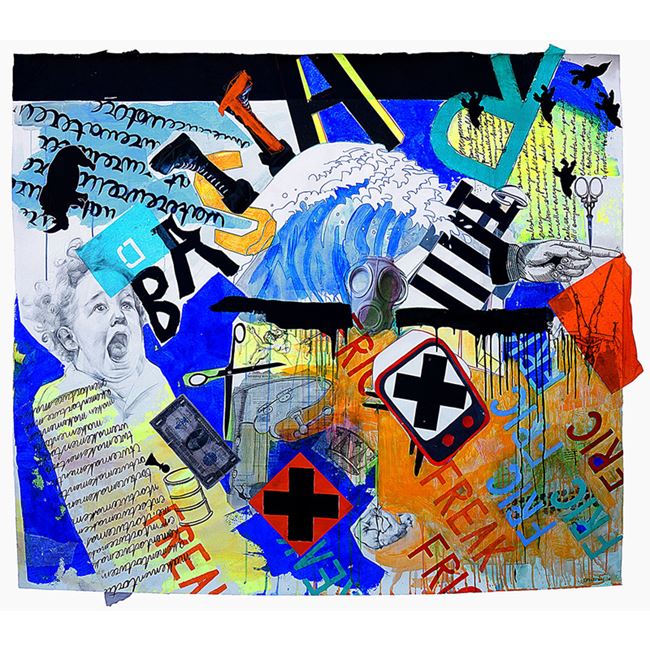

The next evening, we met up at the New Acropolis Museum to make our way to the poshe district of Kolonaki, where Zoumboulakis Galleries was hosting the opening night for an exhibition of modern art by Christophoros Katsadiotis and Jenny Kodonidou. The displays were respectively titled: “Poetic Incidents” and “Notes on Ambiguity”.

It seems that most people had come to the gallery to socialize and enjoy a glass of wine. We stood before each piece, as we had in other museums, and tried to interpret them, but all of our attempts were speculative, haphazard, and contradictory. What a contrast to the experience of contemplating the icon!

Eventually we had an opportunity to question the artists who were both there that night. Kodonidou told me that she cannot express herself well in words and so she uses art. Katsadiotis refused to tell us what any of his pieces meant saying that he did not want to lend any of his own rationale for it because he prefers to leave everything up to his viewers’ perceptions.

I am reminded of the first chapter on the “Objectivity of Beauty” in Dietrich von Hildebrand’s Aesthetics, newly published in English translation by the Hildebrand Project. Hildebrand explains, “Every attempt to present beauty as a product of our own response [emotional, affective, intellectual…] is a clear contradiction of the facts. Value-responses always presuppose the perception of a value on the side of the object. […] Beauty reveals itself unambiguously as something adhering to the object and not as a mental state which takes place in us.”

It is as C.S. Lewis said in his “Meditation in a Toolshed“: “But you can’t think at all – and therefore, of course, can’t think accurately – if you have nothing to think about.”

In The New Philistines, Sohrab Ahmari criticizes contemporary artists for whom the true measure of their art is political power. He says, “The question is never, ‘Does this piece of art express something true, beautiful, or good?’ or even ‘Do I enjoy this?’ Rather the relevant questions are: ‘Who gets to express what?’ and ‘Who gets to evaluate?’ […] The desire to be universally legible is among art’s oldest and noblest impulses. And yet, among the identitarians, it is considered a great sin. One motivation for dismissing legibility may be that contemporary art is often illegible…”

Many at that gallery that night were doing precisely that: dismissing the criterion of legibility.

Art need not be completely explicit or realistic; however, it should be legible, capable of being understood. Ahmari makes the points abundantly clear saying, “To put it concretely: why am I addressing this book to you? It is, of course, because I want to communicate something – how I feel, what is on my mind, what I see in the world and so on. I want this book to be legible, for as many people as possible to appreciate it, whether or not they agree with its arguments.” A good artist intends to communicate, not obfuscate.

Not all of us who stood before that painting of the Crucifixion in the Byzantine Museum are Christians, albeit we live in a Christian culture. Still, the painting was intelligible to each of us and to all of us on a meaningful level that was borne out by its resonance and by our capability to discuss it in a common language. Good art has a two-fold objective and subjective dimension. There is an objective value that summons us to reverence, reflection, wonder. After all, we cannot truly be moved if there is nothing intrinsically moving by which we can be moved.